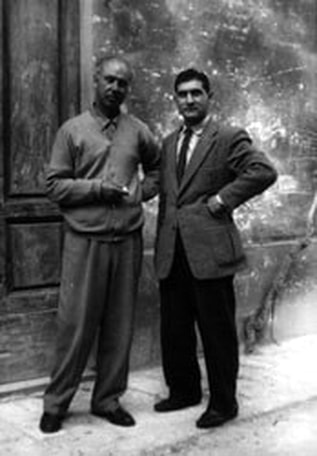

Stanley Lewis in Florence

by Andrew Bailey

The American writer Irving Stone (1903-1989) is perhaps best known for his book The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961), a biographical novel about Michelangelo (1475-1564), which was later turned into a film (1965). What is less well known is that Stone derived most of his information about Michelangelo’s carving methods from the Canadian sculptor Stanley Lewis (1930-2006). Stone acknowledged this in the notes to his novel, writing that Lewis “was my guide in Florence to Michelangelo’s techniques; there he also taught me to carve marble. He has answered an unending stream of questions about the thinking and feeling of the sculptor at work”. This friendship between Lewis and Stone is a rare and interesting example of collaboration between an artist and a novelist, and undoubtedly contributed to the success of the book.

Lewis was in Florence researching and studying Michelangelo. He had come to Florence on a grant from the Greenshields Foundation in Canada, to develop his own skill as a sculptor and to add to his portfolio of work. Lewis enrolled in the studio of Vittorio Gambacciani, whom he called his Maestro, and who still practised the ancient techniques of marble carving.

Stone came to Florence at around the same time, also to research the life and work of Michelangelo. He used the streets and churches of the city as material for his novel, studied art in the museums, did extensive background reading, and made acquaintance with Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), the connoisseur of Italian Renaissance art who lived at Villa Tatti near to Florence.

by Andrew Bailey

The American writer Irving Stone (1903-1989) is perhaps best known for his book The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961), a biographical novel about Michelangelo (1475-1564), which was later turned into a film (1965). What is less well known is that Stone derived most of his information about Michelangelo’s carving methods from the Canadian sculptor Stanley Lewis (1930-2006). Stone acknowledged this in the notes to his novel, writing that Lewis “was my guide in Florence to Michelangelo’s techniques; there he also taught me to carve marble. He has answered an unending stream of questions about the thinking and feeling of the sculptor at work”. This friendship between Lewis and Stone is a rare and interesting example of collaboration between an artist and a novelist, and undoubtedly contributed to the success of the book.

Lewis was in Florence researching and studying Michelangelo. He had come to Florence on a grant from the Greenshields Foundation in Canada, to develop his own skill as a sculptor and to add to his portfolio of work. Lewis enrolled in the studio of Vittorio Gambacciani, whom he called his Maestro, and who still practised the ancient techniques of marble carving.

Stone came to Florence at around the same time, also to research the life and work of Michelangelo. He used the streets and churches of the city as material for his novel, studied art in the museums, did extensive background reading, and made acquaintance with Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), the connoisseur of Italian Renaissance art who lived at Villa Tatti near to Florence.

Lewis’ Maestro, Vittorio Gambacciani, possessed a plaster cast of Michelangelo’s Tondo Pitti from which Lewis made a marble copy, now in the possession of Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts. In a letter to his mother, Lewis wrote that this Michelangelo copy would demonstrate to everyone that he had had “a proper classical training”. The Tondo Pitti is partially unfinished, possibly because Michelangelo wanted viewers to see how the work had been created and to appreciate the marble for its own sake; and this may have been a factor which attracted Lewis to make a copy of it. Lewis loved marble as a medium and created an innovative series of sculptures in coloured marble. But Lewis’ use of marble for his sculptures also worked against him, because the use of this material made his work seem old fashioned back in Canada. As Lewis wrote to his mother, modern taste was for avant-garde “weird and welded metal toys”.

When Lewis discovered that Irving Stone was in Florence, he contacted him and they arranged to meet. They had already met briefly in Mexico when Stone had bought one of Lewis’ prints. The friendship and collaboration between the two men was beneficial to both of them.

Over a two-year period (1957-58) Lewis gave Stone a great deal of information about sculpture in general and Michelangelo’s techniques in particular. He took him to the studio of Vittorio Gambacciani and gave him lessons in carving marble. For his part, Stone repaid his young friend by inviting him to dinners, at which they discussed art, lent him books, and introduced him to Bernard Berenson. And it was Stone who chose the title for Lewis’ most important sculpture, The Pink Lady.

According to Renaissance art theory, forms were imprisoned in the blocks of stone and crying out to be released by the sculptor. Michelangelo wrote that “we give to rugged mountain stone a figure that can live, and which grows greater when the stone grows less” (poem 152). Lewis expressed a similar thought when he wrote in a letter to Stone that “creative form . . . is realised by the slow process of peeling off layer after layer”. An idea repeated by Stone in his novel: “Bringing out the live figures involved a slow peeling off, layer after layer” (The Agony and the Ecstasy, Book 3, Chapter 8).

Renaissance Italians were keen collectors of fragments of ancient sculpture, because the spirit of the classical past seemed to live on in them. Lewis expressed a similar idea when he wrote to Stone that “ancient carvings are often found broken in several pieces, yet when they are assembled, its spirit, its soul still pulsates”. This idea was used by Stone, when one of the characters in his novel says that “many of my ancient pieces were found broken in several places, yet when we put them together their spirit persisted” (The Agony and the Ecstasy, Book 5, Chapter 8).

These examples demonstrate that Lewis and Stone were not only concerned with the mechanical techniques of sculpture but also with its aesthetics and philosophy.

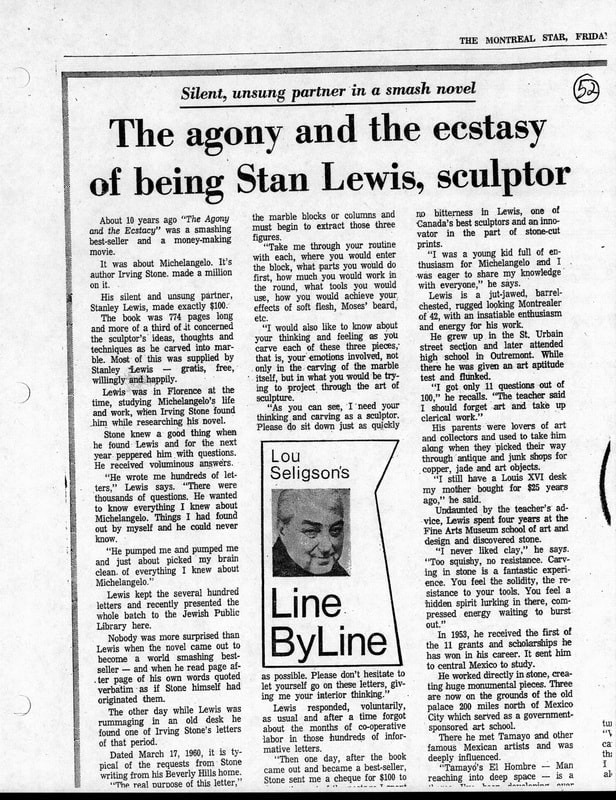

The publication of The Agony and the Ecstasy and the subsequent film made Stone a household name. He was also given an award by the Italian government for his services to culture. His classic novel The Agony and the Ecstasy is still in print and also widely available second-hand. Lewis, however, felt that he himself had not been given enough credit for his own contributions to the book, as shown by the newspaper clipping below:

Over a two-year period (1957-58) Lewis gave Stone a great deal of information about sculpture in general and Michelangelo’s techniques in particular. He took him to the studio of Vittorio Gambacciani and gave him lessons in carving marble. For his part, Stone repaid his young friend by inviting him to dinners, at which they discussed art, lent him books, and introduced him to Bernard Berenson. And it was Stone who chose the title for Lewis’ most important sculpture, The Pink Lady.

According to Renaissance art theory, forms were imprisoned in the blocks of stone and crying out to be released by the sculptor. Michelangelo wrote that “we give to rugged mountain stone a figure that can live, and which grows greater when the stone grows less” (poem 152). Lewis expressed a similar thought when he wrote in a letter to Stone that “creative form . . . is realised by the slow process of peeling off layer after layer”. An idea repeated by Stone in his novel: “Bringing out the live figures involved a slow peeling off, layer after layer” (The Agony and the Ecstasy, Book 3, Chapter 8).

Renaissance Italians were keen collectors of fragments of ancient sculpture, because the spirit of the classical past seemed to live on in them. Lewis expressed a similar idea when he wrote to Stone that “ancient carvings are often found broken in several pieces, yet when they are assembled, its spirit, its soul still pulsates”. This idea was used by Stone, when one of the characters in his novel says that “many of my ancient pieces were found broken in several places, yet when we put them together their spirit persisted” (The Agony and the Ecstasy, Book 5, Chapter 8).

These examples demonstrate that Lewis and Stone were not only concerned with the mechanical techniques of sculpture but also with its aesthetics and philosophy.

The publication of The Agony and the Ecstasy and the subsequent film made Stone a household name. He was also given an award by the Italian government for his services to culture. His classic novel The Agony and the Ecstasy is still in print and also widely available second-hand. Lewis, however, felt that he himself had not been given enough credit for his own contributions to the book, as shown by the newspaper clipping below:

Although not given due recognition in his native Canada, Lewis was awarded a medal by the Italians and the Golden Key to the city of Florence for his contributions to Michelangelo studies, especially for his research into Michelangelo’s techniques. On a more personal level, he wrote to his mother to tell her about the beauty of Italy, the friendliness of the Italian people, and the ways in which his own art had developed as a result of his years in Florence: “I found myself in Michelangelo and Italy”.

Stanley Lewis in Florence

by Lee Lewis. An account.

Lee lives in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada. She first met Stanley while still a student at McGill University, as he was a friend and classmate at Beaux Arts of her former late husband, Sam Gesser. Lee ultimately became Stan’s sister-in-law, when she became Herb Lewis’ partner in 1971. Lee is co-founder of the Mermaid Theatre, Nova Scotia

by Lee Lewis. An account.

Lee lives in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada. She first met Stanley while still a student at McGill University, as he was a friend and classmate at Beaux Arts of her former late husband, Sam Gesser. Lee ultimately became Stan’s sister-in-law, when she became Herb Lewis’ partner in 1971. Lee is co-founder of the Mermaid Theatre, Nova Scotia

I have vivid memories of meeting Stanley’s maestro, Vittorio Gambacciani. My late first husband (Sam Gesser) and I visited with Stanley in Florence in the summer of 1958. (Sam and Stanley had studied together at Beaux Arts in Montreal.) Apart from giving us first hand insights into the intricacies and symbolism of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s masterpiece, The Gates of Paradise, Stanley took us to one of his favourite locales - the nearby stone quarry hill town of Fiesole. We had dinner outdoors on the patio, as the shepherds and their flocks passed just below the walls where we sat – we could hear munching.

We also had wonderful meals in the pensione where Stanley boarded – with the front garden flanked by rows of fig trees. But certainly the highlight of our visit was our time at the Maestro’s studio. Vittorio Gambacciani, in addition to teaching, was primarily involved in making licensed marble copies of masterpieces for museums around the world. (Andrew mentioned the cast of the Tondo Pitti – there were many in the studio ). I have one of the Maestro’s copies, which Stanley brought to Canada and gave to Herb. It’s the celebrated Head of a Faun (my copy attached), rumoured to be one of Michelangelo’s first works. There is a wonderful detailed account of this work featured in this article.

I have an amusing memory related to the wonderful Pink Lady and its voyage to Montreal. Stan and Herb’s mom and principal patroness, the late Anne Lewis, was tasked with underwriting the costs of shipping Stan’s entire oeuvre to Canada once it was time for him to return home. She pleaded with Sam and me to try and convince Stanley to make much smaller works and preferably not in marble – the transportation expenses were horrendous. We didn’t go there. But her palatable joy was obvious at the memorable Musée de Beaux Arts vernisage where the Pink Lady was a star.

Finally: I do have one of Stan’s works which you may not have catalogued. I believe it’s limestone, and was created upon his return from Italy (and possibly after his work in the North of Canada) when he transitioned to the use of Canadian materials. I’ve attached an image of the Head (it stands about 19”).